[Editor's Note: This article is adapted from a May, 2006 article that I wrote for the Williamsburg-Greenpoint Preservation Alliance website. This adaptation includes significant updates on the sugar refining process based on information from an Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) report, American Sugar Refining Company, Brooklyn Refinery (HAER #NY-548) to which I contributed. The full report (which includes great photography by Rob Tucher) and additional images of the building over time are included in the building data entry here at Novelty Theater. Additional information on the history of the site and history and legacy of Havemeyer family is based on subsequent research over the past 12 years.

Subsequent to the original WGPA post, the central refinery building of the Domino site was designated as a New York City landmark. The LPC designation report includes references to the original WGPA post. Since then the Domino site has been rezoned and, with the exception of the main refinery structure, all of the former sugar factory buildings have been demolished (although this article maintains the present tense description from the original article). Prior to demolition, documentation of all of the buildings and systems was carried and recorded as part of the HAER documentation, was completed in 2014, and is now on file at the Library of Congress.

wgpa.us has an extensive collection of articles, photos and other information surrounding the rezoning and landmark designation battles that took place between 2004 and 2010.]

Introduction and Statement of Significance

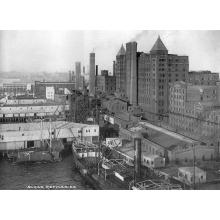

The Domino Sugar Refinery is one of the most prominent industrial sites on the East River waterfront. The complex consists of seven larger buildings and many other smaller structures, occupying a six-block site on the Williamsburg waterfront immediately north of the Williamsburg Bridge. The existing complex includes two buildings from the refinery’s earliest period of construction, 1884, as well as a number of other significant structures from the 1920s-1930s and 1950s-1960s.

At the time of its construction in 1884, the complex was the largest sugar refinery in the world. The refinery continued to be a major processor of sugar into the 21st century. The existing complex includes architecturally and historically significant structures from the 19th and 20th centuries. These include the Rundbogenstil processing house (1885) and Adant house (1875) the industrial moderne raw sugar warehouse (ca. 1930), and the concrete and glass Bin Structure (1960), with its neon “Domino Sugars” sign.

The precursor to the Domino Refinery was founded by the Havemeyer family and the refinery operated under a variety of corporate names, most significantly Havemeyers & Elder and the American Sugar Refining Co. The Domino Refinery was one of the most prominent and significant industrial operations on the Brooklyn waterfront in the 19th and 20th century. The factory was a major source of employment for residents of the Eastern District (north Brooklyn). The Havemeyer family’s presence in Brooklyn began on one block at this site in the 1850s. By the early 20th century, the Havemeyer’s controlled most of the Eastern District waterfront, from the Williamsburg Bridge to the Bushwick Inlet. Their interests in the American Sugar Refining Company led to the development of the Austin, Nichols & Company Warehouse (Cass Gilbert, 1913), the largest grocery wholesaler of its time, and one of the earliest expressive uses of reinforced concrete. The Havemeyer family also developed the Brooklyn Eastern District Terminal (BEDT), one of the largest pocket railroad depots in the country, which served most of the north Brooklyn waterfront, as far inland as Wythe Avenue.

The refinery is nationally significant for its industrial advances, and for the sheer scale of its operations. It is also a nationally significant site for its place in the Havemeyer family sugar trust, which by the end of the 19th century, controlled over 90% of the sugar production in the United States.

Site Description

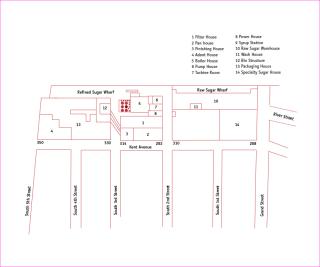

The American Sugar refinery site is bounded by South 5th Street to the south, Grand Street to the north, the East River to the west and Kent Avenue (formerly First Street) to the east. In addition to the properties described herein, the Domino Refinery historically included additional parcels of land on the east side of Kent Avenue; these sites are not included in this survey.1 The existing site is shown on the site plan, below.

The south block (tax block 2427, lot 1), from South 5th Street to South 3rd Street, contains three structures. The Adant House (#4 on the site plan), at the corner of Kent Avenue and South 5th Street, is a four-story brick building constructed in 1875 (and thus the only structure dating to before the 1881 fire). The Bin Structure (#12), at the northwest corner of the block, is a 130’ or so tall concrete and glass structure constructed in 1962. The Packaging House (#13), which occupies the remainder of the block, is a two-story building constructed in ca. 1962.

The center block (tax block 2414, lot 1), from South 3rd Street to South 2nd Street, contains eight significant buildings and a number of smaller structures. The Finishing House (#3), located on the corner of South 3rd Street and Kent Avenue, and the Pan House (#2), located on the corner of South 2nd Street and Kent Avenue, share a common 10-story brick façade that runs the entire length of Kent Avenue between the two streets. The Filter House (#1) is a 13-story brick structure located roughly in the center of the block, running from South 3rd Street to South 2nd Street. Collectively, the Filter House, the Pan House and the Finishing House, all of which were completed in 1884, are referred to as the Processing House. The remainder of the center block contains the Boiler House (#5), the Pump House (#6), the Turbine Room (#7), the Power House (#8) and the Syrup Station (#9). These latter buildings occupy the western portion of the block, facing onto the East River, and were constructed between 1927 and 1962.

The Refined Sugar Wharf extends along the East River from just north of South 5th Street to the north side of South 2nd Street.

The north block (tax block 2388, lot 1), from South 2nd Street to Grand Street, contains three buildings and the Raw Sugar Wharf. The Raw Sugar Warehouse (#10), which runs the full two blocks along the East River, is a two-story brick building with cast-concrete trim constructed in 1927. The Wash House, also constructed in 1927, is located within the footprint of the Raw Sugar Warehouse, roughly 100’ north of South 2nd Street. The Specialty Sugar House, constructed ca. 1960, is on the corner of Grand Street and Kent Avenue. The Raw Sugar Wharf runs the full two-blocks from South 2nd Street to Grand Street along the East River, west of the Raw Sugar Warehouse. The remainder of the block is currently vacant.

The American Sugar Refinery & the Havemeyer Family: A Brief History

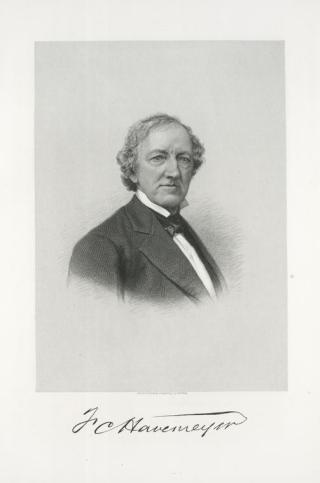

The Havemeyer sugar dynasty dates to 1805, when brothers Frederick C. and William F. Havemeyer founded the William & F. C. Havemeyer Company and opened their first sugarhouse at 87 Vandam Street in Manhattan. The brothers were German immigrants, trained in the sugar refining business in their home country. Upon their arrival in the United States at the turn fo the 19th century, they worked briefly at the Edmund Seaman & Co. Sugar Refinery on Pine Street before opening their own concern.2

In 1828, this first generation of Havemeyers passed the ownership of the refinery onto their respective sons, Frederick C. Havemeyer, Jr. and William F. Havemeyer, Jr. The sons operated the Vandam Street refinery as Wm. F. & F.C. Havemeyer, Jr. Co. until 1842, at which they transferred ownership to their respective brothers, Albert and Diedrich Havemyer. In 1849, Albert and Diedrich brought William Moller into the partnership and the firm subsequently operated as Havemeyes and Mollers.3

On leaving the firm in 1842, the Havemeyer brothers embarked on different careers. William F. Havemeyer, Jr. entered politics, serving three terms as mayor of New York City (1845-46; 1848-49 and 1873-74). Frederick C. Havemeyer traveled extensively in Europe, primarily studying sugar refining in England and Germany. On his return to the U.S. around 1855, Frederick formed a new partnership with his son George and Dwight Townsend. Operating as Havemyer, Townsend & Co., the firm leased a warehouse on the Williamsburg waterfront at South 3rd Street and Kent Avenue.4 . At that time, Williamsburg was a fast-growing city that had been incorporated into the City of Brooklyn the year before.

The move to Williamsburg marked a significant change in the scale of operations for the Havemeyer family and for the entire sugar refining industry. At Vandam Street, the firm produced about 4,000 pounds of sugar a day. Immediately on opening the Brooklyn refinery, production increased to 300,000 pounds a day, and by the early 1870s, over 1,000,000 pounds per day. This massive increase in capacity was brought about by Frederick C. Havemeyer’s combination of a number of innovations into a single, large-scale operation:

In the mid-19th century, the sugar refining industry was transformed by the development of a number of new technologies. These included the development of the vacuum pan in London in 1812. The vacuum pan allowed a more rapid crystallization of sugar by reducing the boiling point to below 212°F. This eliminated burning and caramelization of sugar that occurred in traditional boiling, and thus resulted in pure white sugar. About the same time, the use of bone black as a filtering agent was adopted. In the 1820s, a centrifugal machine was developed to separate sugar crystals from the molasses coating that was left behind in the refining process. The final technological development was the invention of a granulator system that dried moist crystals by blowing hot air over them. (Havemeyer, Merchants, 15.)

While he did not invent any of them, Frederick C. Havemeyer, Jr. is credited with being the first refiner in the U.S. to combine these four new technologies into a single plant. It is likely that he saw these new technologies in operation in his travels to London, where he also studied the business of refining very closely. Because all of these processes required large amounts of space, water and fuel, as well huge outlays of capital, their consolidation in a single new plant “made all inland refineries obsolete”(Havemeyer, Merchants, 16.).[blockquote]5

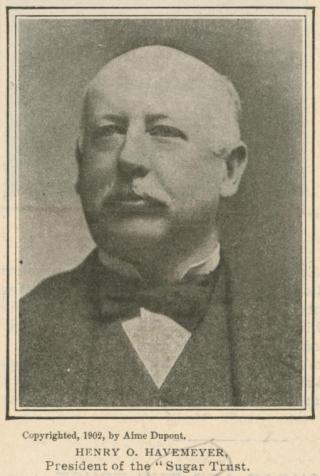

From 1856 to 1882, the main building of the Havemeyers refinery was located on Kent Avenue between South 3rd and South 4th Streets. In 1859, the company expanded the refinery south to South 5th Street and constructed a cooperage (probably on the other side of Kent Avenue). In 1861, George Havemeyer died in a refinery accident. In 1863, Townsend left the firm for his own career in politics (he would two terms in Congress), and that same year Frederick C. Havemeyer, Jr. formed a new partnership with a second son, Theodore A. Havemeyer and a son-in-law, J. Lawrence Elder, to form Havemeyers & Elder. Upon Elder’s death in 1868, Frederick’s third son, Henry O. Havemeyer, was brought into the partnership along with a nephew, Charles Senft.6 The firm continued to operate under the name Havemeyers & Elder, and under the leadership of brothers Henry and Theodore would soon transform the industry anew.

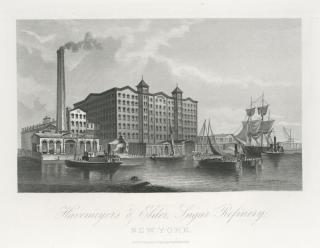

By 1882, the Havemeyers & Elder complex included a 10-story brick refinery building (1857) on the East River, and a 13-story cast-iron boiler house across Kent Avenue. In 1880, Havemeyers & Elder acquired the idle Wintjen, Dick Harms Refinery, a 13-story structure located on the East River between South 2nd and South 3rd Streets and embarked on plans to construct a new and even more efficient refinery on that site.

In 1882, as plans were being completed for the new refinery, a catastrophic fire destroyed the 10-story brick sugarhouse between South 3rd and South 4th Streets. Havemeyers & Elder quickly set about rebuilding and expanding their Brooklyn operations. Under the direction of Theodore Havemeyer, the company acquired more surrounding property and constructed a new refinery complex extending from South 2nd to South 5th or South 6th Streets. The new Havemeyers & Elder refinery opened in 1884 and included a 13-story processing house between South 2nd and South 3rd Streets, on the site of the former Wintjen, Dick refinery, and a 6-story packaging house (later the Adant house), located on the corner of South 5th and Kent Avenue.

The Adant house and the processing house still stand, and the latter remains the most prominent structure on the American Sugar Refinery site. At the time it was constructed, the Havemeyers & Elder refinery was the largest sugar refinery in the world in terms of production capacity; at that time, the City of Brooklyn was the “greatest sugar manufacturing city in the United States,” with 20 major refineries responsible for processing more than half the country’s sugar7 . The site continued to expand and evolve over the course of the next century. At its peak, the refinery employed over 5,000 workers.

In 1887, 17 of the largest sugar refiners in the country combined to form the Sugar Refineries Co., a trust company based in Massachusetts. The new company was headed by Theodore Havemeyer and represented 75% of the country’s sugar refining business. In addition to Havemeyers & Elder, the Sugar Refineries Co. included the following Brooklyn refiners: Decastro & Donner (which operated 3 refineries, including one at South 9th Street and Kent Avenue); Havemeyer Sugar Refining Co. (located on the Greenpoint waterfront and operated by a cousin of Theodore Havemeyer); Brooklyn Sugar Refining Co.; Dick & Meyer Co.; Moller & Sierck Co.; and Oxnard Brothers Co. With the exception of the Brooklyn Sugar Refining refinery and the Havemeyers & Elder refinery, all of the other Brooklyn refineries were closed down.8

In 1891, Harry O. Havemeyer, another son of Frederick C. Havemeyer, reorganized the Sugar Refineries Co. as the American Sugar Refining Co. In 1902, American Sugar registered the Domino brand name for the first time (the brand actually originated with the Decastro & Donner firm).

In 1917, the refined sugar warehouse and packaging house were seriously damaged by fire. Beginning in 1927, the site underwent a major renovation, which included the construction of the boiler house and the raw sugar warehouse (both of which remain today). Another major construction project was begun in 1960. This included the construction of a new wharf, the packaging house, shipping and warehouse facilities, the bin structure and the specialty sugars house, all of which stand today.

In 1970, American Sugar changed its name to Amstar Corp. In 1988, Tate & Lyall acquired Amstar’s American Sugar Division and renamed the company Domino Sugar Corp. Domino Sugar was subsequently acquired by the Florida Crystals Corp. in 2001 and incorporated into their American Sugar Refining Co.9

In 2002, Domino Sugar stopped processing raw sugar cane at its Brooklyn Refinery. Starting in that year, partially processed liquid sugar was brought to the refinery by boat, and the refining process was completed in the Pan House and the Finishing House. In 2004, Domino ceased operations entirely at the refinery and sold the property. At the time of its closing, Domino and its predecessor corporations was the longest operating industrial user in Brooklyn, having operated continuously on the Williamsburg waterfront for 148 years.

The Sugar Refining Process10

The centerpiece of the American Sugar Refinery site is the massive processing house, located on Kent Avenue between South 2nd and South 3rd Streets. This structure consolidated three operations within a single building. The largest part of the structure was the Filter House, which was located in the 13-story portion of the processing house, in the center of the block between Kent Avenue and the East River. The refining process was organized vertically, using the gravity to pass a slurry of raw sugar from floor to floor, and at each floor refining the slurry a bit further. By the time it reached the base of the Filter House again, the sugar was fully purified and ready for processing.

The first stage in the sugar refining process took place at the point of harvest (typically in the Caribbean, Louisiana and Florida). There, cut sugar cane was pressed to produce cane juice, which was boiled into a supersaturated solution that was crystallized into “raw sugar”.11 Raw sugar was brown in color and was not filtered; as a result, it contained many contaminants including sticks, dirt, insects and cane fibers. The raw sugar was packed into hogsheads (barrels) and shipped to Brooklyn for refining.

Raw sugar was brought into the refinery from the East River piers in hogsheads.12 The barrels were emptied into a large mixer vats full of water, which were located in the Wash House at pier level. From the mixer vats, the water and sugar were passed through a large sieve to a second vat below. This wooden sieve caught the large pieces of wood from the hogsheads and other debris but allowed the raw sugar and most other dirt and debris to pass through.

From these mixer vats in the Wash House the sugar solution was pumped up to the top of the Filter House. At the tenth floor, the sugar and water were dumped into large metal “blow up” tanks 10’ high by 8’ in diameter. The slurry of sugar and water was filtered through a “a thick layer of lime mixed with the blood of cattle”13 at the bottom of the blow up tanks and drained through a hole in the floor into long cylindrical-shaped bag filters.

These bag filters were lined with two layers of canvas. The blood and lime in the vat above served to thicken the impurities in the slurry, which were then caught in the canvas bags. The slurry, which entered the bags black in color, was, after filtration, a pale yellow color. .14 The liquid sugar passed from the canvas bags to another metal tank on the floor below; a “slimy mud” left behind in the bags was dumped into metal carts and disposed of.

From the initial filtration at the top of the Filter House, the sugar slurry then passed into two-story tall cast-iron tanks lined with bone char. These tanks, located at the sixth and seventh floors, removed many of the impurities that gave the sugar its color, leading to the much-desired white-colored sugar.

The majority of the space within the Filter House was not used for processing sugar, but rather was for processing and revivifying the bone char that was the primary filter medium in the sugar refining process. Large ovens, two to three-stories tall, occupied the central portion of the Filter House. The ovens were supplied with coal that came from boats directly adjacent on the river and which was stored in large coal hoppers between the Filter House and the river. The bone char - literally charred animal bones - was generally good for a day’s filtration, after which was moved to the ovens, burned, and reused. The kilns and hoppers that revivified the bone char occupied the first through fifth floors of the Filter House.

Following filtration through the bone char, the sugar slurry was passed to vacuum pans located on the floor below in the Pan House. The vacuum pans were large tanks with wide pipes sticking out of the top and connecting it to a cylinder-shaped condenser tank. After the vacuum pan was filled with the slurry of sugar and water, copper pipes that ran through the pan were filled with hot steam. This caused the water in the slurry to turn to vapor and pass through the large pipe at the top of the pan and into the condenser. The sugar was left in the vacuum pan, eventually becoming the thickness of honey.

This thick molten sugar was passed through a hole in the bottom of the pans to cylinder-shaped centrifuges on the floor below. The centrifuges consisted of sieve with wire sides and a copper base, roughly 2’-6” high and 3’-6” in diameter. The sieves were set into an iron case, two to three inches taller and two to three inches wider than the sieve. When the machines were turned on, the sieves spun at high speed, and the last of the water was drawn out of the slurry, leaving a thick 4” layer of sugar lining the sides of the sieve.

From the centrifuge, the sugar was passed through the floor to the Processing House, the third section of the main refinery building, where it went into a large horizontal screw-shaped granulator. The sugar passed over this granulator, and into a stream of hot steam. This process was repeated a number of times, further drying the sugar and separating it into fine granules.

At the time of its construction, the Processing House of the Havemeyers & Elder Sugar Refinery contained six mixers, 12 blow ups, 25 bag filters (which used 10,000 bags per day), 8 vacuum pans, 48 “centrifugal machines”, and four granulators.

Architectural Description

The Processing House and Adant House are constructed in what is referred to as Rundbogenstil, or round arch style. Rundbogenstil was a style that originated in Germany in the 1840s and 1850s and became popular with German émigrés and German-Americans in the United States in the latter half of the 19th Century. As its name implies, the style is based on the use of the round arch as a structural unit. In the United State, Rundbogenstil is often confused with the Romanesque Revival, which was popular from the 1850s through the 1880s. In contrast to the Romanesque Revival, Rundbogenstil was usually more elaborate – and more directly Germanic - in its decoration.

The round arch was a typical feature of storehouses along the southern Brooklyn waterfront, from Fulton Ferry to the Atlantic Basin in Red Hook. In these storehouses, the round arch had the functional benefit of allowing taller openings for loading purposes without the need for less structurally stable flat lintels. The round arch was more expensive to construct than a segmental arch or flat lintel, and was therefore much less common in north Brooklyn, where factories, not storehouses, dominated. At the Havemeyers & Elder buildings, the decoration of the façade, with its prominent brick piers and corbelling, was considerably more elaborate than in the storehouses of south Brooklyn. This level of decoration was quite rare in other round arch industrial buildings in Brooklyn.

The 1884 Havemeyers & Elder did not have an architect in the sense that we think of the word today. The refinery was designed by Theodore A. Havemeyer, who worked with enginer John Van Voorst Booraem and builders Thomas Winslow and J. E. James. The building essentially consisted of load-bearing brick walls enclosing the three functional sections of the refinery, with a separate internal structural system of cast iron carrying the loads of the equipment and machinery, much of which is integral to the interior structural system of the refinery.

The exact inspiration for the style of architecture chosen is not known. The style itself was popular in Germany, and therefore may have resonated with the Havemeyers. It also appears to have been the style used in the old Havemeyers & Elder refinery, destroyed by fire in 1882.

The Processing House is constructed almost entirely of red brick, laid in American bond, with projecting brick ornament. The window sills and a string course at the second floor are constructed of bluestone. The round arch windows have three courses of brick soldier courses around the perimeter of the arch. The inner course is laid in the same plane as the surrounding wall. The center course has alternating projecting and recessed bricks that create a toothed profile. The outer band of bricks are set at a 90° angle to the center band and are laid flush with the projecting brick of the center band. Pendants at the base of the brick arches are created with trimmed brick, set horizontally and corbelled.

The façades have projecting brick piers at the corners and along each the façade, creating vertical divisions. The Kent Avenue façade of the Pan and Finishing House is arranged symmetrically with three outer bays of two window each in width flanking a center bay nine windows in width. The north and south facades of the Pan and Finishing House have a 1-3-1 arrangement, with single window end bays flanking a center bay, three window bays in width.

The Pan House and the Filter House have projecting brick stringcourses. These are located above the fifth floor on the outer bays of the east elevation, and above the ninth floor on all three elevations. The wide center bays on the three elevations have a second cornice below the ninth floor.

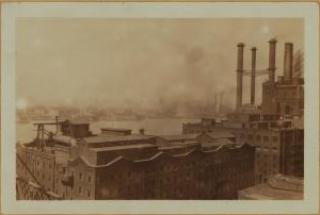

Photo: Brooklyn Historical Society

The west (river) façade of the Filter House has a similar symmetrical composition top the Kent Avenue façade, with a slight variation in the arrangement of bays. This façade has a 2-3-2-7-2-3-2 arrangement. The northern and southern bays, each 2 window bays wide, were originally capped with pyramidal roofs set on a projecting corbelled brick cornice. These towers were removed sometime before 1928. Pyramidal parapets capped the centermost 2-window bays. These parapets were removed sometime after 1928. The center of the west elevation is dominated by the boiler house smokestack, which rises almost twice as high as the Filter House itself. The base of the smokestack, up to the roof level of the Filter House, is original. This portion of the stack has similar corbelling and decoration to that found elsewhere on the buildings. The distinctive brick oval stack that rises above the roof of the Filter House was constructed before 1936.15 This stack is more plainly detailed than the rest of the building, with a simple corbelled brick cornice at the top of the stack and a series of 8 metal bands spaced vertically along the stack.

The north and south elevations of the Filter House have asymmetrical arrangements. The western bay on each façade has two closely-spaced windows (and were originally capped with pyramidal towers described above). The center bay has two widely-spaced windows. The eastern bay has one window only. The east elevation of the Filter House (above the Pan/Filter House) was reconstructed at an unknown point in time and now has an undecorated brick façade with flat-lintel windows.

The corner towers of the Filter House have projecting brick stringcourses above the fifth floor. All three facades of the building have a unifying brick stringcourse above the eighth floor.

The American Sugar Refinery Complex includes at least one other building that dates to the 19th century. This is the Adant House, a four-story structure running along Kent Avenue from South 5th to South 3rd Streets. The Adant House, named after the process by which sugar cubes were produced, was also constructed in 1884 in the Rundbogenstil. The building was originally six stories tall with a pedimented parapet running the length of the building on Kent Avenue. (The pediment was a unifying element in the original 1884 complex of buildings, appearing on every building at that time.) The parapet and upper two stories were taken down sometime after 1928.

The Power House is located immediately west of the Processing House on South 2nd Street. The architecture of the building suggests that it dates to the period of original construction of the Havemeyers & Elder Refinery, 1884. The Power House is a two-story gable-end brick structure. The gable end has corbelled brick work similar to that seen in historic photos of other buildings from the original refinery complex.

The next oldest structure on the American Sugar Refinery site is the Boiler House. This six-story building is located on the East River between South 2nd and South 3rd Streets, immediately west of the Processing House and south of the Power House. The boiler house was constructed in about 1927, and replaced an earlier boiler house dating to 188416 . At the same time, the distinctive oval-shaped double chimney that rises above the Processing House was constructed. This stack, a Williamsburg landmark in its own right, replaced an earlier stack that served the old boiler.

The Raw Sugar Warehouse, a two-story structure located along the river between South 2nd and Grand Streets, was constructed in 1927. This Moderne brick building was designed by the engineering firm Stone & Webster]17 and replaced an older raw sugar warehouse in the same location. The Raw Sugar Warehouse is one-story tall along the waterfront, with a setback second story behind. The warehouse is constructed of brick with horizontal sting courses and copings of cast stone or concrete. Large loading bay entries face the river on the west elevation of the one-story portion of the building. Wide industrial steel-sash windows face the river at the set-back second story. Narrower steel-sash windows are located on the second floor of the north and south elevations. The east elevation has no fenestration. The Wash House is contained entirely within the Raw Sugar Warehouse.

The Raw Sugar Warehouse was the starting point for the sugar refining process. Ships would bring raw suage, primarily from Caribbean ports but also from elsewhere around the world, to the dock in front of this warehouse for unloading. From there, the raw sugar was washed and loaded into the Filter House to begin the refining process described above.

In 1962, American Sugar Refinery completed construction of the Bin Structure, the new Packaging House and the Specialty Sugar House. The Bin Structure and Packaging House replaced earlier buildings that were part of the original 1884 Havemeyers & Elder Refinery. The Bin Structure is located on the river at South 3rd Street, south of the Boiler House. The tallest building at the American Sugar Refinery site, the Bin Structure is constructed of reinforced concrete to the height of the adjacent Filter House, with a glass crown roughly four-stories tall. The lower portion of the building is essentially a series of silos for storing processed sugar prior to packaging or loading onto truck for bulk transport. The glass crown of the buildings contains a series of tubes and sifting pans for sorting the different sugar products into the respective silos. The building is connected to the Finishing House by a pair of sloped bridges that contain conveyor belts for moving the refined sugar from the processing house to the Bin Structure for storage. The west elevation of the Bin Structure contains the 40’-tall yellow neon “Domino Sugar” sign. (The refinery had large illuminated signs on the refinery advertising its product to Manhattanites as early as 1930.)

The Packaging House, also completed in 1962, is located along the river between South 5th Street and the Bin Structure. (Except for the Adant House and the Bin Structure, the Packaging House occupies the entire portion of the two blocks between South 5th and South 3rd Streets.) This building is a two-story structure with open loading bays at the ground floor facing toward the river. Refined sugar from the Bin Structure was packaged and distributed via truck or boat from this building.

The Specialty Sugar house, located on Kent Avenue between South 1st and Grand Streets (east of the Raw Sugar Warehouse), was the last major building constructed on the site. It replaced an earlier Bag Reconditioning Building that was used for repairing the burlap bags that transported raw sugar to the site for over 75 years.

[2018 – with the exception of the Processing House, all of the structures described above have been demolished. Some artifacts, including the gantry cranes and the interior column structure of the Raw Sugar Warehouse were salvaged and are now incorporated into an “artifact walk” that is part of new waterfront park located on the former (and rebuilt) Domino wharf.]

- 1These properties are briefly described in the 2014 HAER report.

- 2Harry W. Havemeyer, Merchants of Williamsburgh: Frederick C. Havemyer, Jr.; William Dick; John Mollenhauer; Henry O. Havemeyer (New York: Privately publishes, 1989), 7, 13-14.

- 3John Leander Bishop, Edwin Troxell Freedly, Edward Young, A History of American Manufactures from 1608 to 1860, Volume 3 (Philadelphia, Edward Young & Co., 1868), 152.

- 4The record is unclear on the exact chronology here. One source says that John C. Havemeyer and Charles E. Bertrand operated Havemeyer & Bertrand and were the first to lease property in Brooklyn. Another source states that F. C. Havemeyer, Jr. returned from an extended tour of Europe in 1855 and resumed control of the company, moving it to Brooklyn in the process.

- 5Jørgen Cleemann, Ward Dennis, American Sugar Refining Company Brooklyn Refinery (Washington, DC, Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NY-548), 5-6.

- 6Havemeyer, Merchants, 31.

- 7“Local Manufacturers: The Interesting Process of Sugar Making,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle (August 17, 1884), 10

- 8The Sugar Refineries Co. also included the North River Sugar Co. in New York City, which was also closed down.

- 9It is not clear if this American Sugar Refining Co. is related to the American Sugar Refining Co. founded by Harry O. Havemeyer in 1891

- 10The following section is excerpted largely from “Local Manufacturers: The Interesting Process of Sugar Making,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle (17 August 1884) 10. Changes to operations subsequent to 1884, as described in the 2014 HAER report, are noted.

- 11Jørgen Cleemann and Ward Dennis, American Sugar Refining Company, Brooklyn Refinery, (Washington, D.C., Historic American Engineering Record (HAER No. NY-548), 2014), 15.

- 12From the late 19th century until the 1960s the plant used burlap bags to ship the raw sugar. Starting about 1960, raw sugar was shipped in bulk in cargo holds. The existing gantry cranes at the Raw Sugar Wharf were installed in the early 1960s to unload raw sugar directly from cargo holds.(HAER, 15)

- 13 “Local Manufacturers: The Interesting Process of Sugar Making” (Brooklyn, N.Y.: Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 17 August 1884), 10.

- 14In the early 20th century, the bag filtration system was replaced by Sweetland filters and string filters, which were located on the 10th floor of the Filter House. The Sweetland filters were horizontal cylinders with cloth-covered frames that were coated in diatomaceous earth. The slurry was passed through the frames, and the combination of the cloth and diatomaceous earth removed impurities. The resulting mud slurry was then processed in the string filters, which separated the diatomaceous earth from sugar water.(HAER, 19)

- 15During the 1920s and 1930s, three massive cast-iron smokestacks dominated the refinery. These were removed by 1936, when the oval masonry stack was constructed.

- 16The 1884 boiler house contained “30 or 40 boilers” at the time of its construction. “Local Manufacturers”, page 10.

- 17Jørgen Cleemann, Ward Dennis, American Sugar Refining Company Brooklyn Refinery (Washington, DC, Historic American Engineering Record, HAER No. NY-548), 14.